"He Wouldn't Take No for an Answer": Ernie Miller on Schofield and The Generator's Origins

Local historian and former Loughborough University associate director Ernie Miller reveals the extraordinary story behind The Generator building and the visionary educator who created it

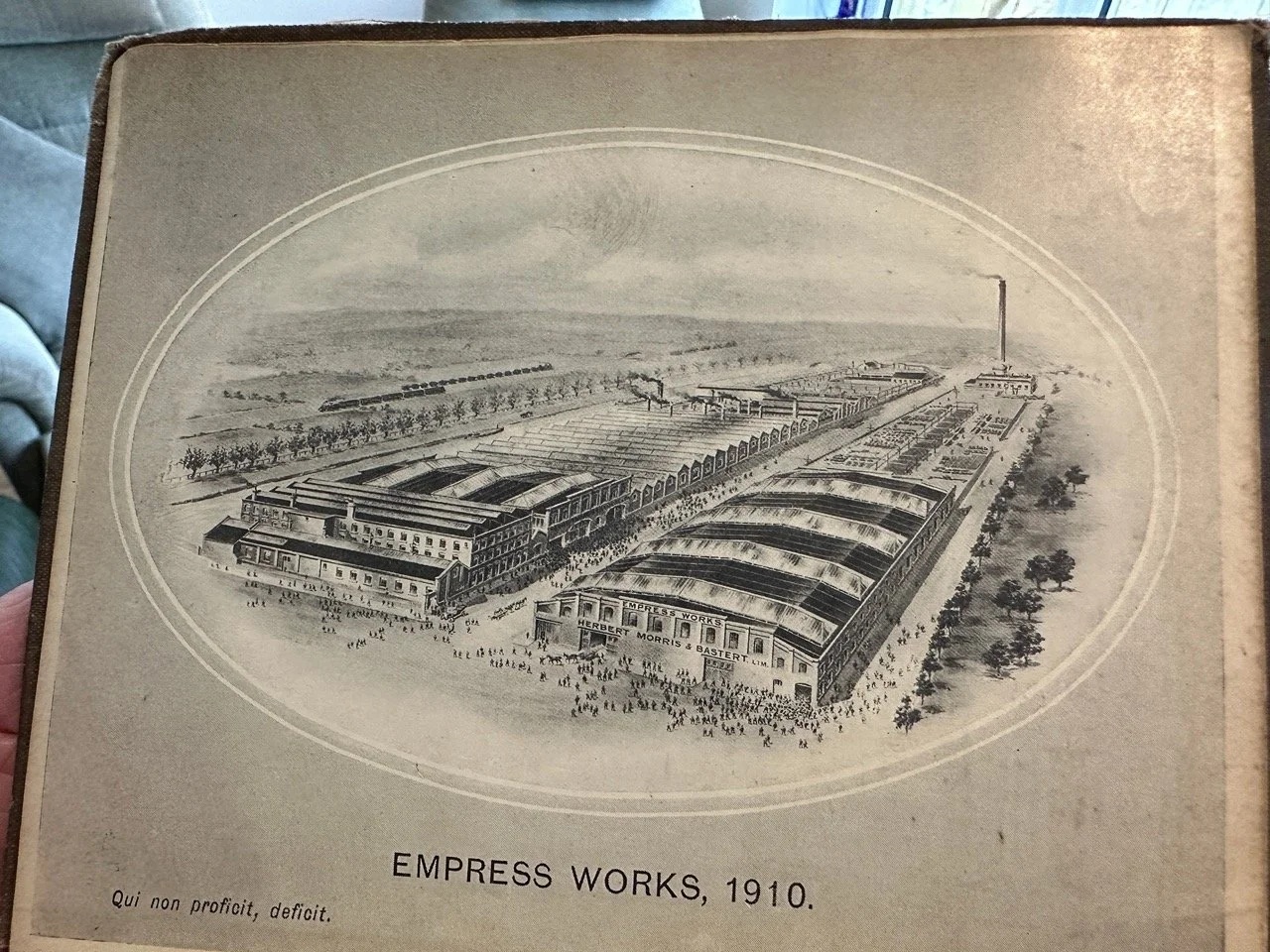

Ernie Miller has spent decades piecing together the history of Loughborough's educational institutions. As a former associate director of staff training at the university and passionate local historian, he knows the stories that official records often miss. When we asked him about The Generator building, he had tales that sound almost too incredible to be true – German submarine engines, midnight power outages, and a man who got his own American car serviced as part of "training on production."

Colin Salsbury, interviewed by Pasha Kincaid

Ernie, can you tell us about the context of Schofield and The Generator building?

Ernie: Well, Schofield was a very complex man. He wouldn't take no for an answer, and he got his own way. One of the things he did was create what we now call The Generator. In its day, it housed two generators from German submarines.

He immediately realized the potential of these engines. He got his engineers – because he was training them – and made arrangements with the military to go down to Devonport to pick up the engines and generators from two German submarines that were going to be scuttled in the Channel.

How did he actually get hold of these submarine engines?

Ernie: Well, they went to Devonport with a couple of lorries and students from the engineering department, but the staff there wouldn't let them touch anything. If you weren't a member of Devonport Dockyard staff, you couldn't touch anything. So they had to come away empty-handed.

But of course, Schofield had a word with somebody – nobody got in Schofield's way. They went back to Portsmouth later, and there was a member of staff there with a great big spanner showing them around. Every time he passed a nice gauge with a glass front, he'd smash it and say "Rubbish! You Germans are rubbish!" – because we'd just won the war.

They had to restrain him after a bit, but finally Schofield got his two complete generators.

What kind of generators were they?

Ernie: I assume they were DC generators, because you wouldn't have had AC on submarines in those days. The clever thing was they generated 110 volts DC, but actually in two chunks of 55 volts with earth in the middle. So between two wires you'd get 110V DC, but at any point down to earth – if you had a fire or something – you'd only get 55V, which is most unlikely to cause a problem.

So this was straight after the First World War?

Ernie: This was around 1935, actually. They'd been running wooden hut generators before that – Schofield was very keen on wooden huts. Students and staff assembled the whole thing. Having two generators meant you could have one being serviced while the other was running. And servicing them was part of the electrical engineering course – students did it as part of their training.

That was his principle: you learn on the job. Training on production.

The college had electricity before many houses in Loughborough?

Ernie: Oh yes! There were college buildings with electricity before many of the houses in Loughborough had it. I know one amusing story about that. Loughborough generated its own electricity in a building where the Rushes shopping area is now. One night the Loughborough system went down and the whole town went black – but it was fairly obvious which were the university buildings because they stood out like Christmas trees. All the ones on Frederick Street, William Street, Pike Street, Green Close Lane were lit up while Loughborough was in darkness.

I read in the Loughborough Echo from around 1928 – the letters to the editor didn't rate the council very highly. They said, "Why don't we let the college provide the electricity? Because they can do it better than the council can!"

What about the building itself?

Ernie: The front part that fronted onto Frederick Street – I'm glad to see you've taken out some brickwork that was put in much later, because there were garage doors all across the front. That's where the college kept its vehicles and serviced them. And would you believe, the man himself had a big American car which he had serviced there on regular occasions. I don't believe any bills went anywhere, but he had his car serviced. Because it was training on production – so why not?

What was left behind when the college moved?

Ernie: They left quite a lot of stuff. One of the buildings nearby actually had in its roof space the wing of a 1914 fighter plane, because they were making them – training on production, training young women. We have pictures of the young women making those. But there was one wing left behind, and it just went with the demolition.

Can you tell us about some of the other interesting features?

Ernie: There was Peter Waals' library next to The Generator. Waals was a well-known arts and crafts designer who they'd persuaded to come to Loughborough in 1935. He died in 1937. These chairs we're sitting on are dated 1937 – I'm fairly sure they were designed by Waals but made under his successor, Edward Barnsley.

He designed this library, students made it with the staff, and then it was moved up to what's now the Manzoni building. When they didn't want all the furniture, one of the lecturers sent a lorry with students down and took all the chairs and refectory tables up to Faraday Hall. They're still there as the high table.

What about the stained glass you mentioned?

Ernie: They had stained glass everywhere because there was a stained glass course with stained glass lecturers. If you go around Hazlerigg-Rutland campus, the stained glass artwork is lovely. And if you look at the people in the windows, then find old photographs, you'll see those faces – they're real people, not just shapes.

When they moved to the new campus, they used almost every bit of that stained glass, but they didn't reuse all the figurative pieces. I haven't seen it for about 25 years, but it was in the stores in huge wooden crates.

Tell us about these chairs we're sitting on.

Ernie: Every student had to work for half a day every week for the college. No ifs, ands, or buts. You got yourself down to the workshop and did whatever the instructor told you to do. If you were making a chair, you made the complete chair.

To make sure they did a good job, you had to put your name on the back rail. And they all did good jobs – these are dated 1937. If you run your finger over the joints, you'll feel where the wood has shrunk. Wood shrinks that way and that way, but not lengthways. So this bit comes up – that's 87 years' worth of shrinkage.

If you're ever doubtful about old furniture, find a joint like that and run your finger over it. That tells you it's genuinely old.

What strikes you most about Schofield's approach?

Ernie: He was always ahead of the game. They changed to British generators in 1935, generating 240V AC, which was becoming the standard. Bit of a shame they did it then, actually, because when Loughborough went from DC to AC, anybody with DC equipment got it replaced with equivalent AC equipment. He could have had a whole load of new kit, but he did it ten years before that. He was always thinking ahead.

The man just wouldn't take no for an answer. If Schofield wanted something done, it got done.