From Student to Ceramics Market Pioneer: David Salsbury’s Generator Journey

We spoke with sculptor-turned-ceramicist David Salsbury about his student days at The Generator, midnight laser escapades, and building Loughborough's thriving ceramics community

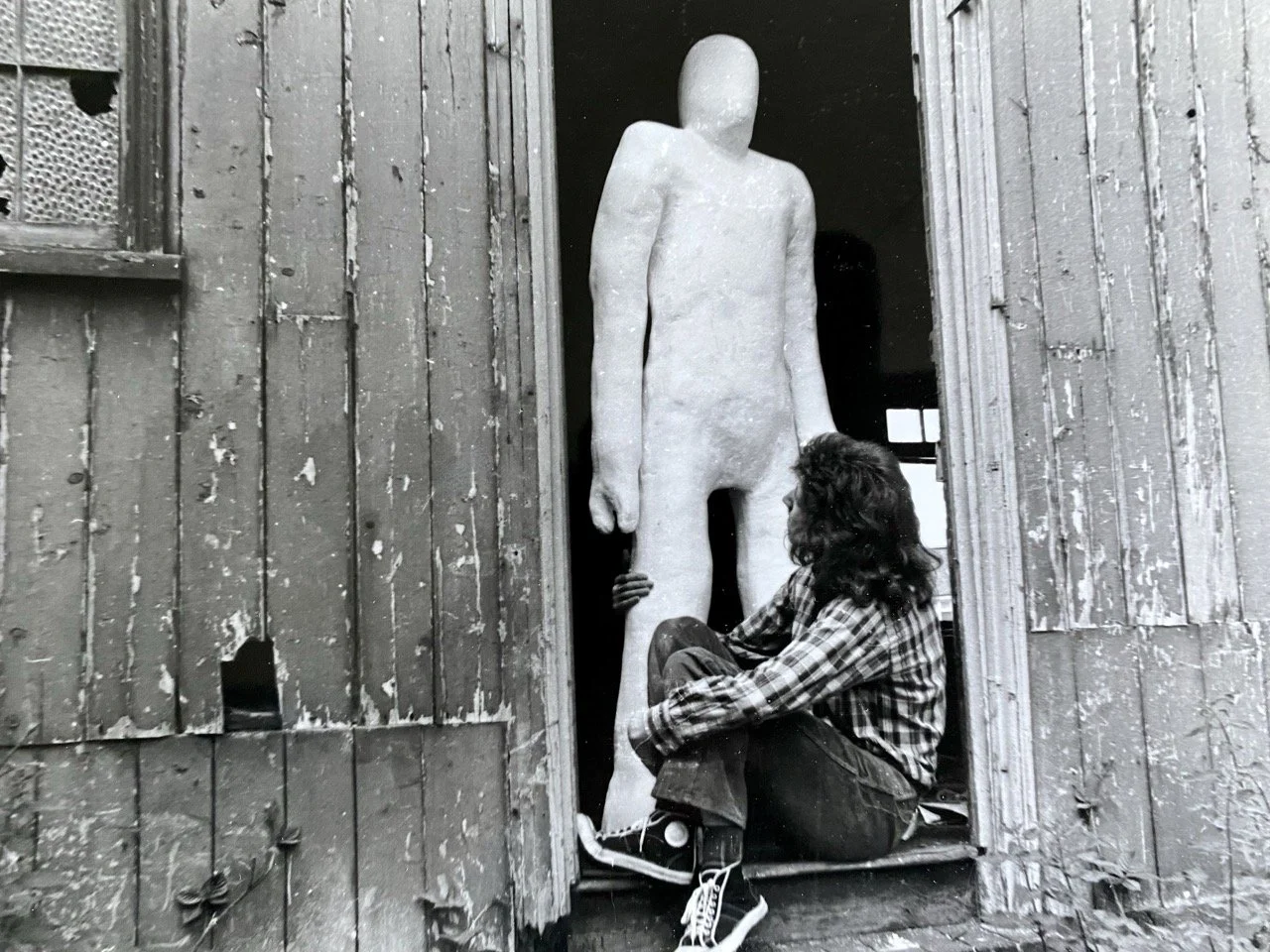

David Salsbury embodies the ripple effect of arts education. A sculpture student at The Generator from 1972-1975, he's now a successful ceramicist who founded Ceramics in Charnwood – a market that brings 90 potters to Loughborough annually. His story traces a direct line from those formative years in the building's industrial spaces to a lifelong commitment to nurturing creative community.

David Salsbury, interviewed by Pasha Kincaid

David, you studied sculpture at The Generator from 1972-1975. What drew you to that building?

David: When I first started in fine art, we had to do a term of painting and then a term of sculpture before choosing our discipline. After two terms, I chose sculpture, and it was really the building that attracted me. It had such a lovely industrial past to it, and it just seemed a nicer place to work than the poky painting studios across the way in William Street.

What's your strongest memory of the space?

David: Walking through the storeroom and coming out of a door onto the balcony of what's now the generator gallery, and just being amazed at the wide space that was there. Looking down at these – I suppose they must have been transformers or something with lights inside them. It was just like being in an ocean liner or something. It was an amazing space.

How do you think that building influenced your work?

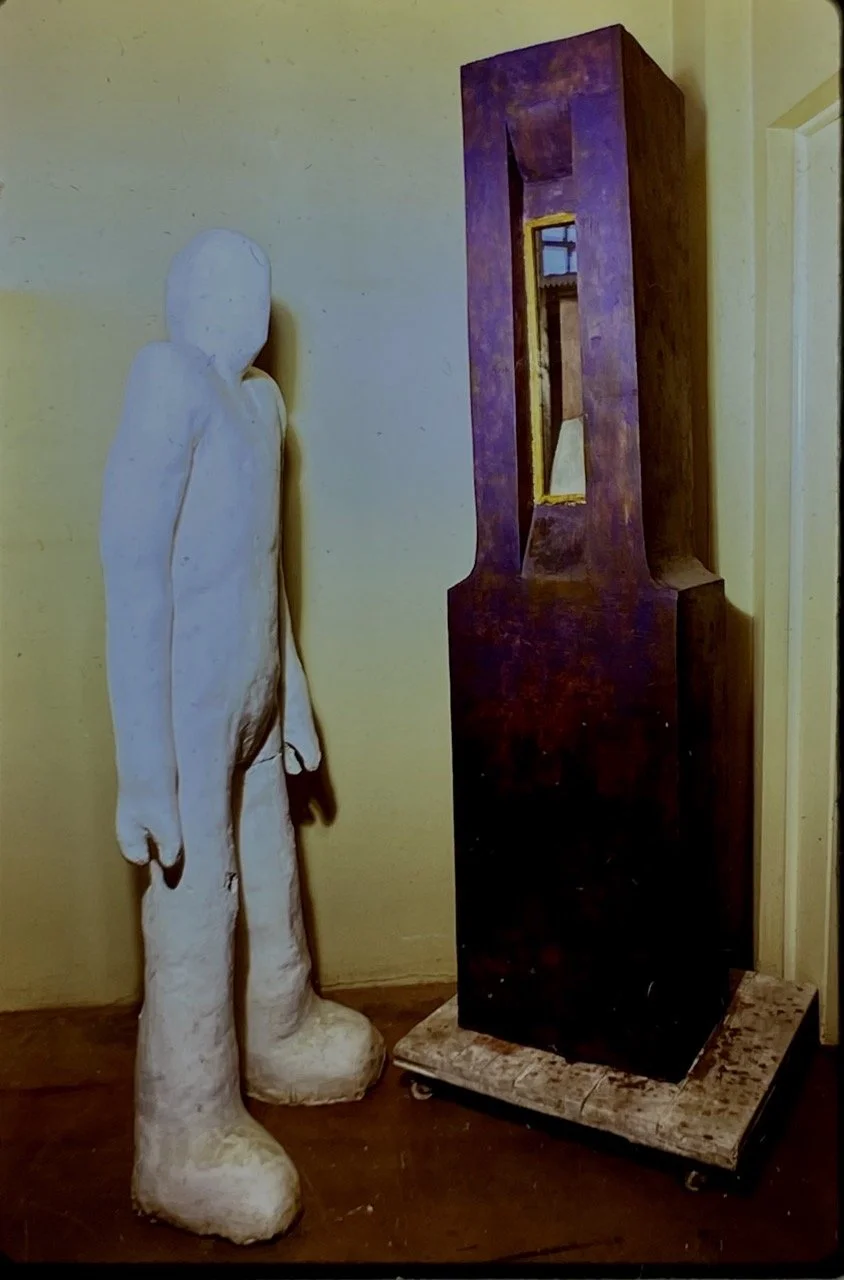

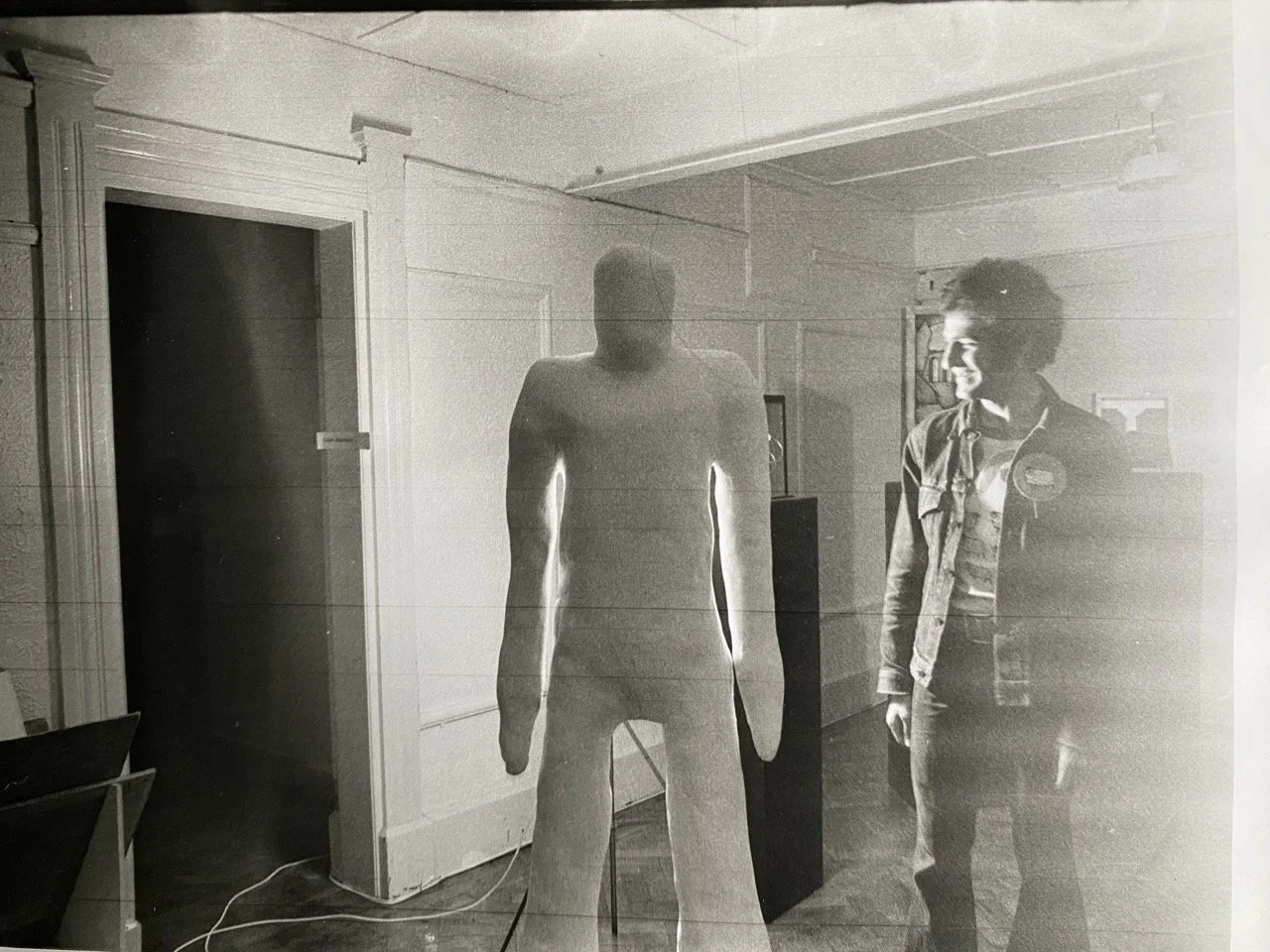

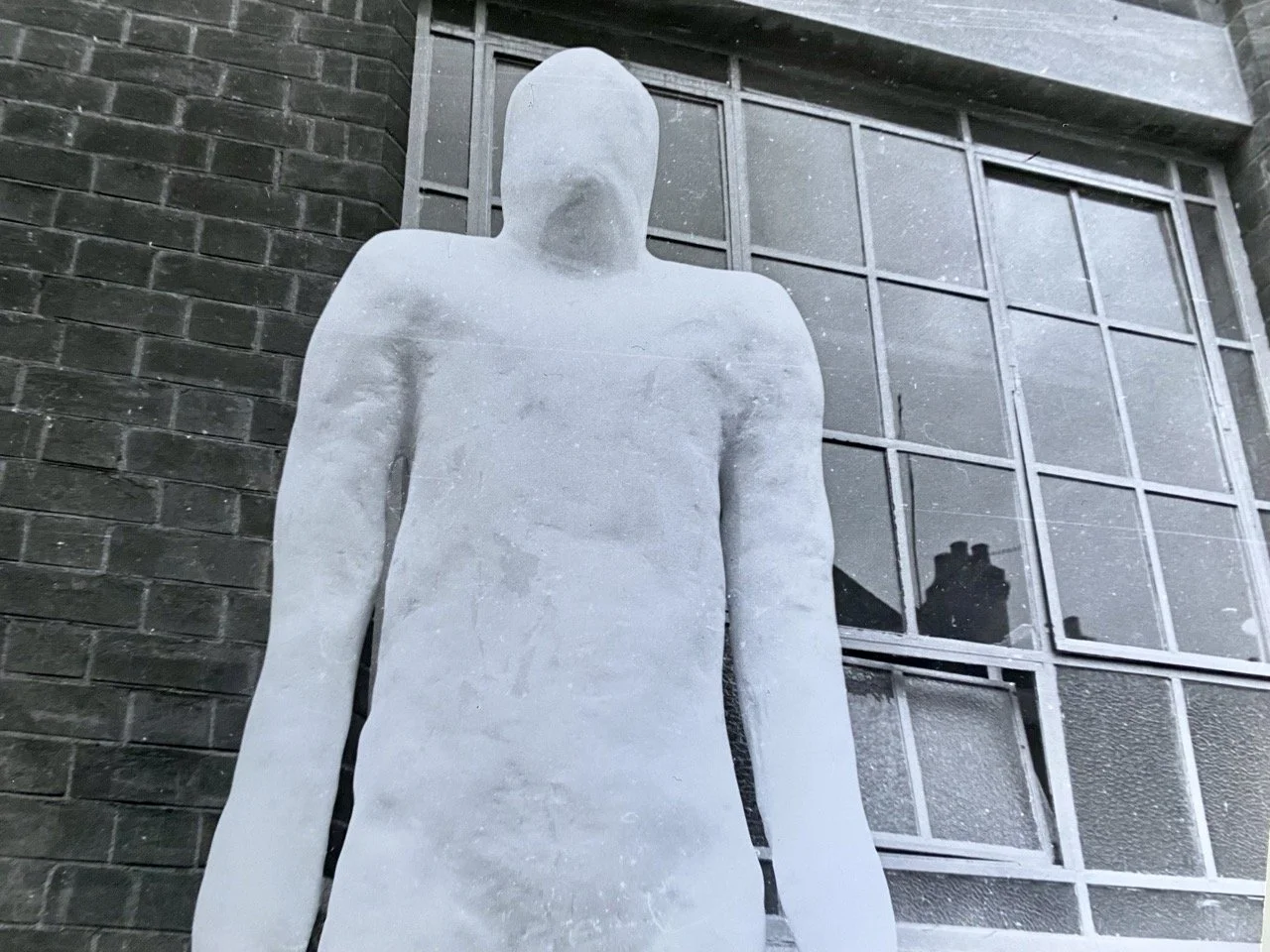

David: My work as a sculptor is all about partly the future and partly the past – it's a combination of the two. Being in that building certainly made you feel as though you were part of some kind of futurist landscape. It must have influenced me.

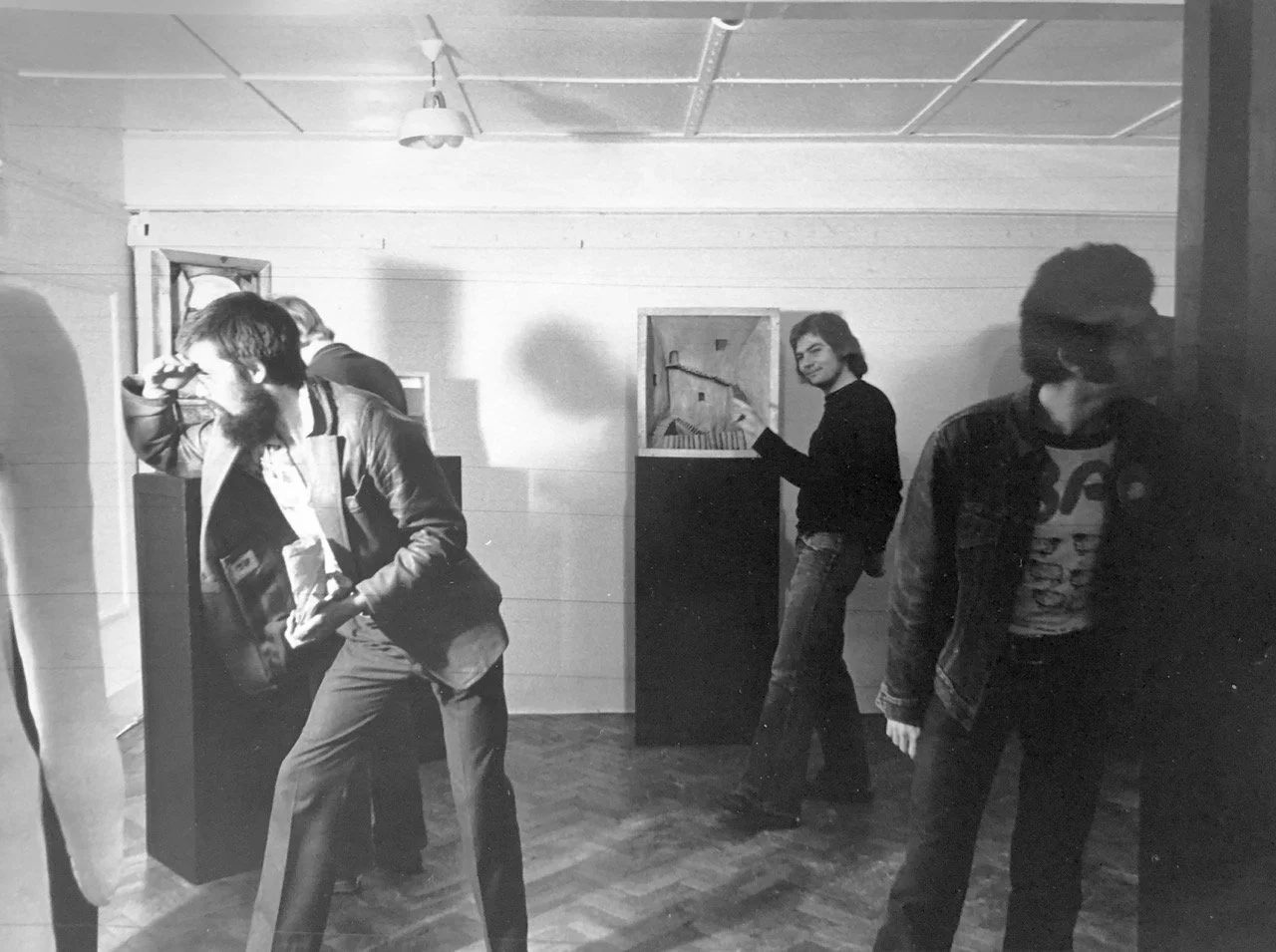

What facilities did you have for sculpture?

David: Being part of Loughborough College before it became the Art College, there was a machine shop on the ground floor where we had metalworking tools and machines. Things like band saws for cutting out big chunks of wood. There were wax and plaster modeling areas, all in this lovely open space on the ground floor.

Then through the door into the generator area at the back, we had a forge and kilns for burning out wax for casting. We had equipment for molding, for casting metal – bronze and alloys like that. I remember some of the tutors casting in bronze using sand casting and lost wax. We all had to watch the demos when they were done.

Tell us about your tutors. Were they practicing artists?

David: My personal tutor was Bob Scriven, and he made welded metal figures. On his days off, he'd be building something on the ground floor with a torch, cutting metal and welding it together. The head of sculpture, Dave Tarver, was pretty much a stone carver, and John McGill as well, but more traditional. They carved the fountain in the middle of Loughborough marketplace – I think their names are on it.

You had to study complementary subjects too?

David: We all had to do design options – I think two days or two evenings a week. We could choose from silversmithing, jewelry, furniture making, and ceramics. I chose ceramics, which led to a career in the industry and as a potter myself later in life. We also had to study music theory and practice, which led to forming a band and playing live. I still play music today.

So the complementary studies really shaped your future?

David: It was just a great big absorbing of information all through the course. I remember the art history lectures being really vivid – learning all about painters and sculptors in the past, taught by Pete Wheeler, David Miller, and Hugh Jones. I was absorbing this huge amount of information over those three years.

Any interesting stories from your student days?

David: I remember after I left college, it was the night before I got married, and a group of students found a way into the college at night. In the dark, we went up onto the roof and borrowed a laser from the technician storeroom and shone it on the town hall. You could see people trying to follow the light. Of course, we left quietly after that!

The roof was a regular hangout spot?

David: I think we weren't really allowed to be up there, but there was one occasion where a couple of students got married, and after the reception in the pub, we all went up on the roof because it was a nice sunny day. It was a regular spot for sun bathing or playing guitar. Good views as well.

What did you do after graduation?

David: There were really two big options – postgraduate studies or teacher training. Then there were people like me who weren't quite sure what they were going to do, but I knew I wanted to go to London. Eventually I found a job at Fulham Pottery, a really old, traditional pottery in London. I worked there for 12 years and stayed in London for 20 years before coming back to the Midlands to start my own ceramics business with my wife.

What kind of ceramics do you make now?

David: I've specialized in tile making because I love to paint on the ceramic surface. Hand-painted tiles are my specialty, but I do make a few jugs and bowls and decorate those as well. It was actually the experience of using clay at Loughborough and finding out you could paint on clay that rang a bell. It wasn't really for another 5 or 6 years until I had the time to try it for myself.

You founded Ceramics in Charnwood market. Tell us about that.

David: About 15 years ago, my wife and I decided we wanted to do something in the town to celebrate ceramics. Since Loughborough has its own marketplace, we decided to get all our pottery friends together and stage a market. It's happened every year since then and gradually grown – this year we've got 90 potters coming in May.

How did you build that community?

David: I go out and do events in other places, like ceramic festivals. You meet people, get to know them, and gradually they find out what you're doing and they're quite happy to come and give it a go. All the potters and ceramic artists are different, so it works.

What's your vision for The Generator now?

David: The thing I'd love to do is put on a ceramics fair in the building where I first started. That would be amazing. But I'd also like to see music events and exhibitions there. I think as long as it's not too exclusive – it would be nice to include everybody in the town to come and visit and take part in events there.

Do you remember the local culture around the college?

David: The Griffin pub, which was just behind the Art College, was a meeting place for a lot of the teaching staff pretty much every evening. We used to go there as well, and we'd all go to Tony's Coffee Bar on Market Street for our tea breaks. The Griffin was always a place to go for a drink when we could afford it.

Was there interaction between sculpture and painting students?

David: Most of my friends were in the painting department, so there was a lot of interaction between the two buildings. The sculpture department was on Frederick Street, there was a car park, then the painting department on William Street. I'd be there every week looking at what everyone was doing. We also had to do printmaking in some huts outside the main building – etching, lithography, and screen printing. There was a lot of toing and froing between the two departments.

Do you know what other students from your time went on to do?

David: Two of my friends are still involved in the film industry as scenic artists and prop makers. One friend, Carmel, is a big window display artist for people like Louis Vuitton – he's working on a window display for them at the moment. Others went into education – my friend Terry Shave became head of fine art at Nottingham Trent University. My friend Stephanie became a jewelry designer and still makes jewelry in Cornwall. I've kept in touch with a group of them, and we've all been involved in being creative in some way.